Postmortem: Deeper

Deeper is my second game for Tiny Mass Games as well as my second project in Godot and my second time using my phone to make a game. It is an action-esque, turn-based, extraction RPG. It is a GameBoy aesthetic party-based battle system with time bars instead of mana.

Features

- An Extraction RPG that fits the GameBoy aesthetic and control limitations.

- Control up to four characters at the same time, each with six different moves, using only left / right and A / B!

- Fight 9 Common Enemies and 3 Unique Bosses, each with their own unique mechanics.

- Collect 50+ pieces of procedurally generated equipment and outfit your party.

- Be careful! If characters die, their bodies and, more importantly, their loot are lost to the dungeon.

- (Collect unique equipment that can only be found once.)

- Unlock new color palettes to spice up later runs.

You can play the game on itch.

I originally intended for this game to be a smaller piece of a larger thing, but ended up not completing the larger thing.

What Did I Do On My Phone

I started this game on my computer with a plan to do certain features or types of work on my phone: Tasks without audio, easy systems that didn’t require too much debugging, or better yet, creating Resources and doing basic data entry. That got thrown for a giant loop when my house was flooded and I lost said computer. (And the walls, stairs, washing machine, water heater, files, and more. Big things to lose, but away they went!)

- This game was entirely pixel art, so again I was able to use Pixel Studio Pro to create all of the graphics. This includes:

- 6 Hero Designs (Simple back of head only)

- 6 Enemy Designs, 3 of which having 3 color variations.

- VFX

- Equipment Icons

- UI

- Logos

- Created all equipment resources, both code and the data files.

- Created a virtual GameBoy wrapper that is only available on an Android device. On Android the game is forced into portrait and the controls all sit just below the fold, so to speak, on a regular windowed build.

What I Did On a Computer

I knew going into this one that I would have to make builds on desktop. I was going to aschew FMOD for this one since I knew the plugin didn’t load on an Android device. My plan this time was to do all of the system code on my desktop and then use my phone to just enter gobs and gobs of data.

Luckily I had a laptop I could do builds on, but everything else was via phone.

What I Learned

-

Godot Shaders

Not sure this is a full blown learning. Honestly, I think learning shaders is an evergreen process. You can tinker, you can do tutorials, you can learn the math. Always there’s new techniques, new pieces. For my purposes, what I learned was how to use Godot to write a shader. I already understood the basics of shaders, and I’ve used GLSL before. In this case, the shader was for the colorization of the GameBoy sprites.

In order to get four shades of green, I started by setting up a gray-scale color swatch for my pixel art. All of the art in the game is drawn in grayscale using four colors. Then, I wrote a shader to take four defined colors (the shades of green), find the nearest, and render that instead. Here are the characters I created for the game.

Warning: What you are about to see is programmer art. It may scare some viewers. Proceed at your own risk.

And here is what characters look like in game:

This is also the same magic which allowed me to implement palettes. By making those four colors shader parameters, I could change them at runtime thusly:

var colors_as_vectors = [] colors_as_vectors.append(Vector3(palette.colors[0].r, palette.colors[0].g, palette.colors[0].b)) colors_as_vectors.append(Vector3(palette.colors[1].r, palette.colors[1].g, palette.colors[1].b)) colors_as_vectors.append(Vector3(palette.colors[2].r, palette.colors[2].g, palette.colors[2].b)) colors_as_vectors.append(Vector3(palette.colors[3].r, palette.colors[3].g, palette.colors[3].b)) material.set_shader_parameter("colors", colors_as_vectors)(And because I could change them at runtime, you can actually choose what you want your palette to be!)

-

The Theme and Style Settings

Using Control nodes for your game, you can make a pretty powerful UI using Godot. As with any engine, there are things you’ll love, and things you’ll dislike.

What I loved? The ease of setting up the UI. For more straightforward UIs it is a breeze. Once you need Layouts and Containers, then it gets a little tricky to make all the sizes work. Still, that’s merely a learning curve. I made the entire game using Control nodes, because I thought it would give me easier resolution scaling. (And I think it did in the end!)

This did make positioning things when trying to do VFX a little awkward. Control nodes rely heavily on the heirarchy in the Scene Tree. This means there are some rules about parenting sprites that mean you can’t just lerp from hero to enemy. Those were mostly easy to work out, but sometimes required some thought.

However, when it came to the Settings menu, to make it look all cool and on-brand for a pixelated GameBoy game, there was a boar of a task in setting up the Style via the Theme system. I figured it out, but it is a pain in the butt to parse what does what and how to achieve the look you want. Surely, with time, this might be less hard. For this project, it was pulling teeth.

-

The Built-In Audio System

Last time I used FMOD and my audio extraordinairre, Garrett, handled everything on the FMOD side. This time, I knew I didn’t want to use FMOD because I wanted to get the full experience on mobile. I ended up picking up a music pack from Joel Steudler and doing the implementation myself. I liked the music, but I knew that it didn’t quite fit with the vibe I was trying to achieve.

What I ended up doing was using the built in Audio players and using the Pitch Scale to change the feeling of the music. For example, here is the song I started with for the menu.

But when it gets Chopped and Screwed:

What Worked

-

Imaginary Equipment.

Set myself up for success by making things that could be pure data without art. Equipment, for example, only had an icon for it’s type. Not even any kind of sub-typing. We had a sword for any weapon. A shield for armor and accessories. (Because I made them all armor-ish sounding accessories like boots!)

This meant I could just blast that type of content all day, which was good because the game is about loot. There were 22 pieces of equipment, basically for free.

-

All About Status

Let me let you in on a dirty little secret.

…

Everything is a status effect. Each enemy has some sort of unique twist on how you should deal with them. I wanted to encourage people to use their big, powerful attacks on slimes so if you hit them they deal 1 damage to the attacker. I wanted vampires to suck your blood so they restore health when they attack. I wanted a mob of bats to have as many HP as there were bats in the flock. (IE: If there were 8 bats on screen, you had to hit them 8 times.)

Every single one of those things was done via the status effect system.

At first I was going to program those all out with the AI that I had made. (And I still made complex-ish AIs.) But quickly I realized that every single behavior I had planned out would need the exact same hooks as my status effect system had. So then I just went whole hog on it. All I had to do was create an array on the Enemy Resource that contains “Innate Status Effects”. These would be applied on battle start and make it so that enemies can all do cool things.

The slime had a “Reflect Damage” status effect that onAttacked would deal 1 damage to the attacker. The vampire had a “Vampire” status effects that would heal X% (to be defined by any instance of “Vampire”) whenever onAttack was called. You’ll never guess how those bats did it.

Oh, wait, unless you’ve been paying attention. Yes, the bats had a status effect called “Bats” which triggered via onAttacked. All this did was reduce the incoming damage to a max of 1. After applying the damage, I would reset the sprite based on it’s health.

The sprite updating loop here is driven entirely by a status effect because it’s based on the health of the bats. 1HP = 1 BAT.

-

Creating the AndroidBoy

So figuring out the resolution with viewport height and width was great. I made everything in 144 x 160, but can set the scale and make sure it’s big enough to see. The other cool thing about this is that if you set your Control nodes up a certain way, an Android device in portrait isn’t capable of scaling to fit a square window. Here’s where a cool trick came into play.

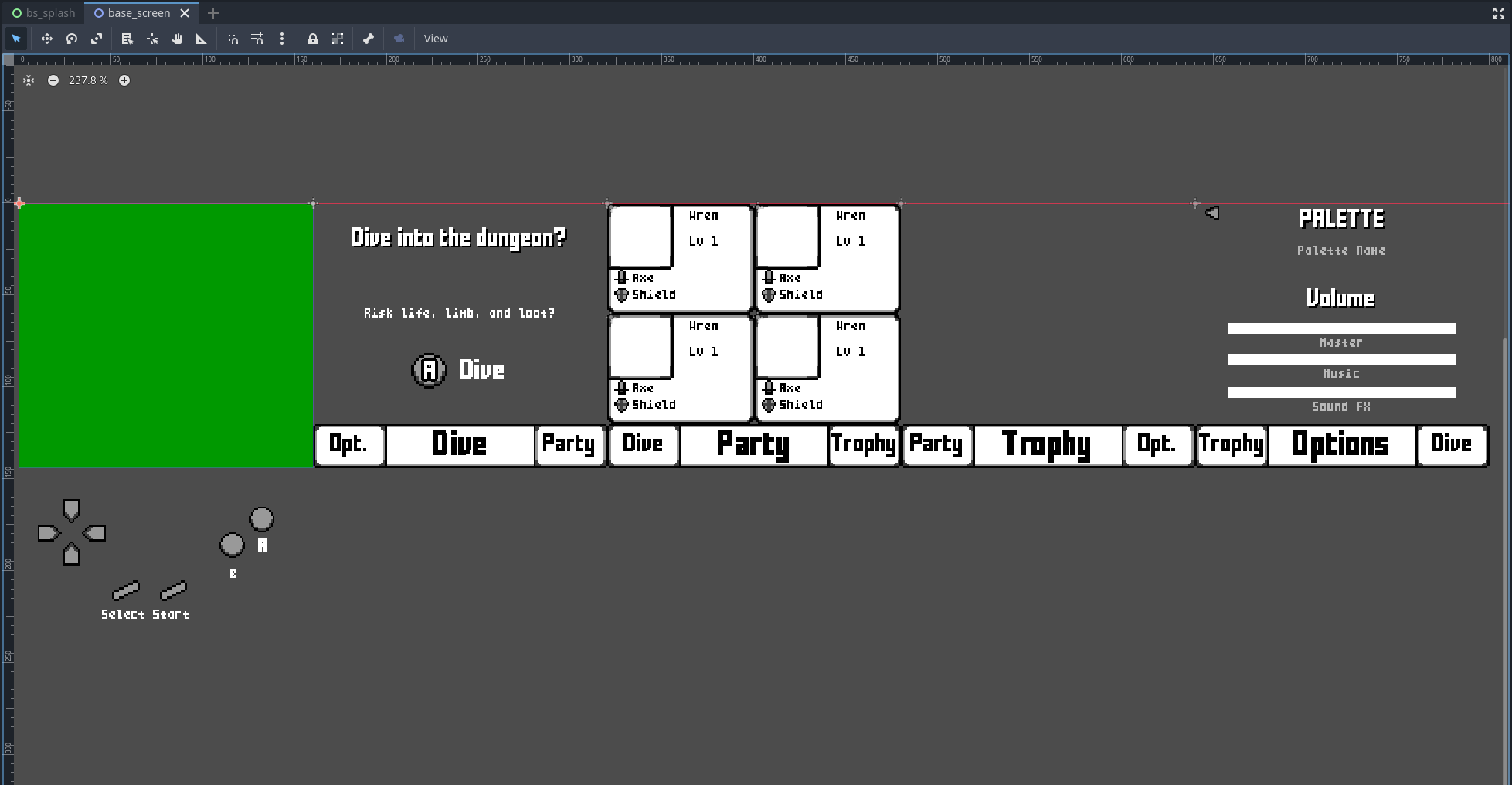

I created debug buttons that would just send input messages. That means if I had one of these debug buttons on screen and pressed it, it would work exactly like if someone were to hit w,a,s,d on the keyboard. So I arranged these debug keys to look like GameBoy button layout and because the Android in portrait would not scale the window large and out-of-proportion, placing said debug button layout directly below the game window means they showed up when you played on Android. And even better, on desktop since it can scale the window and stay square, they just get hidden and cutoff. They’re there just outside the bounds of the window, waiting to be pressed by some hacker. Here they are just below the fold in the Base Screen.

Now, on desktop, because we force a certain resolution and aspect ratio, it looks like this:

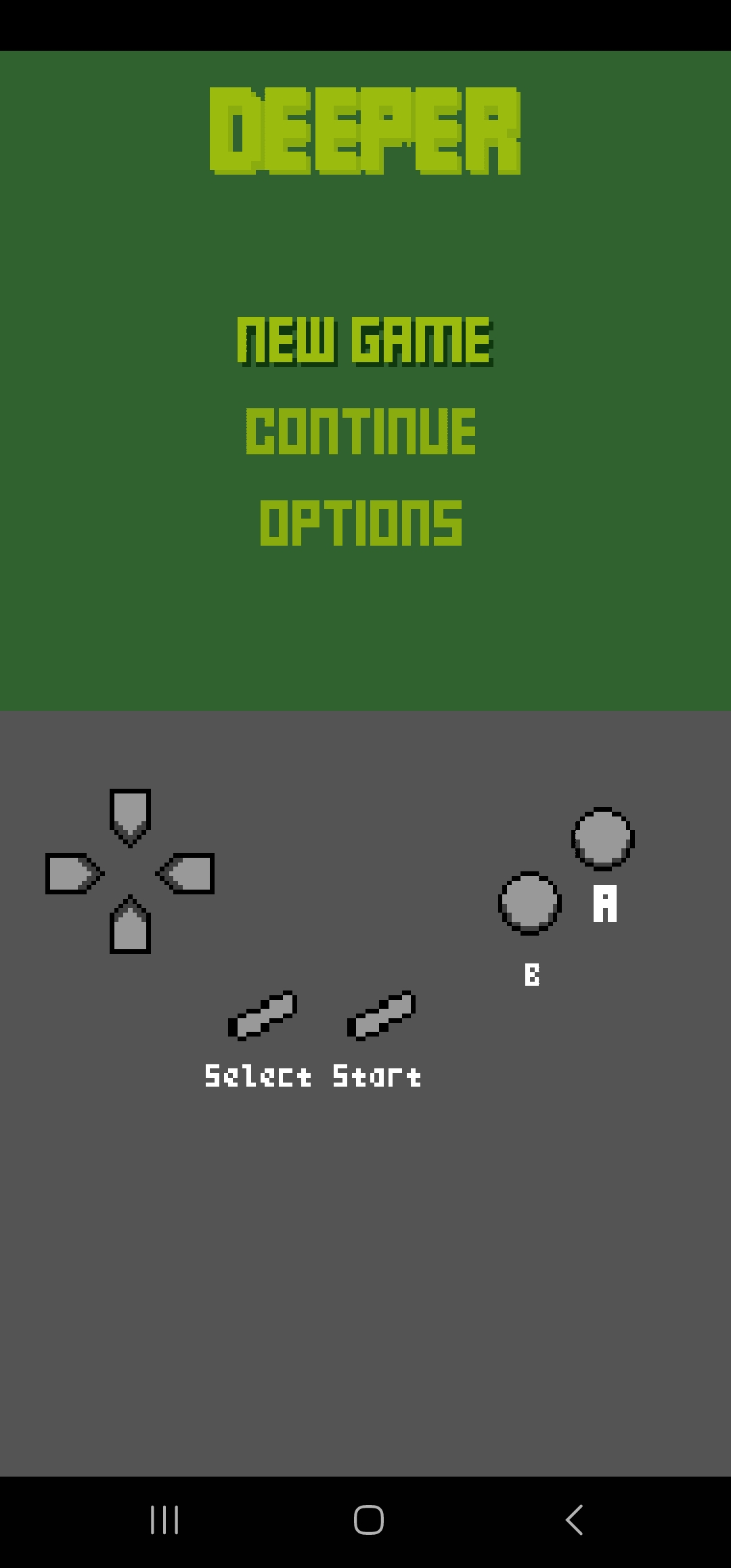

But through the magic of locking resolutions and hiding junk off screen, here is how it appears when you click play on your phone:

What Could Be Better

-

Art!

Listen, I’m not an artist. I’m a card-carrying, practicing programmer. The only reason any of this is even presentable is because I chose a format that has nothing but incredibly low res pixel art and there’s a breadth of reference material.

I looked long and hard at Phantasy Star for the character, back-of-head art. I also made sure to stop at back of head and never show a front. Faces are hard.

-

Needed even more content!

This game is an extraction RPG. Right now there are 22 pieces of equipment in the game, and some of those are actually marked as unique. That means that if you play for a little while, there are less than 20 pieces of equipment to get. Now, you can also find palettes in the dungeon and trophies, so that’s the entirety of the loot set, but I still think if the point of the game is to find equippable loot, there should be more of it.

-

The classes weren’t fully baked.

This kinda falls into the more content category. Creating moves was the most taxing piece of content to produce. Anything unique that it did would require code and testing. On top of that, if I didn’t already have something I could use for the VFX, I had to create animated sprites. I envisioned several classes with movelists of about 8 to 10. I got five classes with 4 - 6 moves each.

I underestimated this one quite a bit and ended up pushing it off to focus on the three bosses in the game instead. I also did some silly stuff like making a bard who has VFX that look kinda like music notes of the actual SFX that are being played. (But again, programmer, so that might be way horrible too!)

In Conclusion

Water sucks.

You can play the game on itch.

I’ve got something of a system going here with making stuff on my phone, and that doesn’t end here on Deeper!